Über bwp@

bwp@ ... ist das Online-Fachjournal für alle an der Berufs- und Wirtschaftspädagogik Interessierten, die schnell, problemlos und kostenlos auf reviewte Inhalte und Diskussionen der Scientific Community zugreifen wollen.

Newsletter

bwp@ Spezial 19 - August 2023

Retrieving and recontextualising VET theory

Hrsg.: , , , &

Let’s avoid tilting at windmills, or Why we are studying vocational education and training (VET) with more than just one theory

Irrespective of how it is rooted in history or regions, VET is such a complex field of social and institutional interaction and so significant to personal development that any approach based solely on research will inevitably prove inadequate. A one-dimensional approach would then produce partial blindness to unrecognised phenomena, or to put it another way: limitations and influential factors remain largely neglected. This article is written from a German perspective and calls for the consideration of interdependencies in VET. It is hence a plea for methodological diversity and ‘theory triangulation’. To this end, it starts by investigating the phenomenon of partial perception, systematises the various levels of vocational education phenomena that should be explored and finally drafts an orientation model. Given this broad scope, it will necessarily rely on shortcuts – touching briefly on subjects that are intended to provide model explanations. The article underscores that objective science and the VET research do not exist. Instead they remain embedded in social practice and will, as a matter of necessity, make decisions in regard to the selection of research tools, the issues at hand and the subjects it intends to address.

1 The way we perceive a subject depends on our perspective

The following section pursues a phenomenological argument and begins by describing a situation in the context of professional actions.

If we gaze at a wall, our perception is shaped by the intentions we associate with the object. Outlines, shades and shapes may or may not become visible, depending on how our thoughts and sensations connect with the object or situation we are currently perceiving. If we intend to lay an electrical cable and are considering the ideal route and the number of junction boxes that need to be installed, the painting by Edvard Munch hanging on the wall may not be of interest, even if we are currently standing in a museum in Oslo. This principle applies to all other objects we encounter and appraise. The phenomena we perceive therefore depend on our intentions, experiences and conscious or unconscious preconceptions, theories and models.

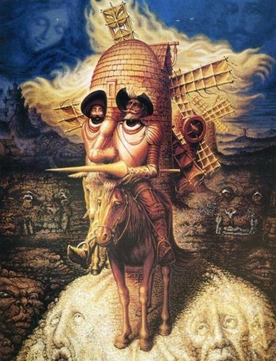

This individual or cultural perception of reality, which also possesses considerable importance for communication theories (Watzlawik 1976), can be used to explain misunderstandings in relationships and to analyse the causes of disputes. Not only does the painting shown in the following illustration depict a literary figure that has found its way into our cultural memory due to its peculiar perception of reality, it also plays with the experience we know from other ambiguous images and visual experiments that, upon viewing, reveal either one or the other dominant perception, depending on age or background (refer to Figure 1). Therefore, we either see two riders in front of a windmill or a bearded face with tussled blond hair. The article is intended to reduce the risk that we end up tilting at windmills by embracing a ‘false’ or one-sided perception of reality.

Figure 1: Octavia Ocampo: Visions of Quixote, oil on canvas, 1989, source: https://www.wikiart.org/en/octavio-ocampo/visions-of-quixote

Figure 1: Octavia Ocampo: Visions of Quixote, oil on canvas, 1989, source: https://www.wikiart.org/en/octavio-ocampo/visions-of-quixote

These preliminary thoughts on perception point to the fact that only a critical reflection of one’s own culturally influenced perceptions and social contexts will allow research subjects to appear in a different light and open the door to alternative appreciations. Vocational training and education is exposed to a historical dynamic of change, like the associated political and social culture. This gives rise to the need for social and discourse-analytical theory(ies) that can take into account the tensions between society, the economy, education, work, professional life, training and power. Only then can we shed light on the negotiation processes involving the state and the economy in VET and avoid premature adaptation of thinking and research to hegemonic discourses.

Where research and development are intended to build curricula to create competence profiles that can be derived from vocational action situations and the associated establishment of training regulations or school curricula, then pedagogical reflections on the goals of emancipative VET and vocational science approaches will remain largely neglected if the focus is placed on teaching and learning theories alone. Conversely, activity and action regulation theories and phenomenologically reconstructed case analyses do not yet enable consideration of the spatial or political dimensions within vocational didactics. Work systems and professional mentalities and cultures can only be decoded, exploited in curricula and translated into educational objectives if their mutual entanglement is established.

Other theoretical points of reference become useful when dealing with the structuring of specific acquisition processes – didactic design in the narrower or concrete sense. In this case, the individual subject and the interactive social dimension of learning together acquire relevance, along with the particular actions of the teacher in regard to their use of techniques, selection of methods, facial expressions and voice etc.

Even these preliminary examples speak in favour of embracing theory(ies) that are appropriate to the subjects they consider, engage in dialogue with them and seek to appraise their entirety instead of just highlighting aspects that are consistent with a theory.

2 Outlining vocational education, or What is the subject we wish to investigate?

A large number of introductions to vocational and business education or brief articles in educational handbooks contain various attempts to define vocational education and the related academic discipline of vocational and business education (Arnold/Gonon/Müller 2015). But the distinction between vocational and business education is not set out in non-German-speaking countries, as they speak merely of ‘vocational education and training’.

Vocational education and training refers to all non-university learning and educational processes that are directly or indirectly related to the use of knowledge, skills and applications acquired in this context for gainful employment. In this regard, learning and education are viewed as a change process that is governed by intention and largely by curriculum, whether by teaching staff, media or self-governed processes embraced by the learner.

This brings into play several factors for the subject area. It is focused on these acquisition and organised learning processes, irrespective of the age of the participants, the institutional boundaries and whether these activities are aimed at obtaining a vocational or further training qualification, are preparatory or build on these things. Included in this are a variety of learning forms such as learning in the workplace – a very common feature in VET – along with all forms of learning in training and further education institutions. The definition impedes the inclusion or exclusion of all manners of informal learning that do not take place as observable learning at the workplace. But their prevalence is increasing dramatically, especially in an age of digitalisation in which learning materials have become more easily accessible and every tutorial on a video channel and every guide to professional success or to building resilience may potentially be relevant to gainful employment.

This definition would exclude all learning and acquisition activities that are not geared towards gainful employment but, for example, towards unpaid care work and cultural, artistic or political activities – a quintessential field of family and adult education whose delineation can be explained by means of political expediency.[1] University and academic education are excluded to enable a simplified distinction.[2]

the definition of VET is shaped by the author’s background in scientific disciplines and lifeworlds and his German context. Other definitions and tasks emerge from the viewpoint of training and labour market research, educational sociology, biographical research, specialist didactics or even an educational science perspective, which prompts the question of which epistemologies are relevant to VET research.

3 The Bronfenbrenner levels as a ‘sorting tool’ for subject areas and studies of vocational education

The following section begins by systematising the phenomena and action contexts of VET with reference to Urie Bronfenbrenner’s socio-ecological model. Within this context, the author is well aware that Bronfenbrenner’s model was originally conceived to overcome deterministic models in the context of socialisation (cf. Epp 2018) and hence focuses on the individual’s engagement with their social environment. “The ecology of human development encompasses the scientific study of the progressive and mutual accommodation between an active, growing human being, and the changing properties of the immediate settings in which the developing person resides. This process is continuously influenced by the relationships between these areas of life and by the larger contexts in which they are embedded” (Bronfenbrenner 1981, 37).

Nonetheless, the model is used frequently to categorise different areas of VET. Current examples include three articles by emerging researchers from different continents at the European Conference on Educational Research (ECER) 2023 in Glasgow, United Kingdom. But even in German research, Adolf Kell was also keen to refer to Bronfenbrenner’s eco-systemic concept in his work into VET and drew on it repeatedly to analyse vertical interrelationships between environmental structures and the learning and working spheres of VET (Kell 2013, 9f.). In doing so, he highlighted that the different spheres or systems in which VET takes place are mutually influential and hence create a specific tension between economics and pedagogy (Kell 2013, 17). An adapted model based on Kell’s subject areas of VET is used in the following to categorise the four levels (macro, exo, meso and micro). Examples of relevant works and studies in VET science are mentioned on these levels, but without addressing the underlying theories and concepts in detail.

This adheres neither to the highly worthwhile distinction made by Kell and van Buer between labour, occupational, educational and vocational education and training science (Kell 2015), nor the distinction drawn by Harney (2020) between historical-comparative, vocational training theory-occupational science, social science and finally psychological-didactic VET research. These distinctions build on current scientific systematics and divisions of labour, which are also accompanied by the distinction between subject areas. But this is precisely the source of their weakness, as these procedures, irrespective of the simplification they produce, adhere to a logic that does not originate from the research subject, but from a configuration of sciences based on division of labour. As a result, the repertoire associated with the sciences, instrumental logic included, soon rises to the fore in place of an approach that would be more appropriate to the subject. Hence, scientific division of labour may well be a response to the requirements of practice, as Harney emphasises in the introduction: “On the one hand, VET responds to a [...] problem of the division of labour and the inherent reliability of the reproduction of societal labour capacity, which is manifest in particular in crises of scarcity and excess. Vocational education and training research is part of this response” (Harney 2020, 640). Research is thus linked with practice for him, but remains restricted to the socio-political and economic perspective. He does prise this open again with reference to psychological-didactic VET research, but becomes nonetheless caught up in a muddle of current studies that sometimes focus on teaching-learning and teaching methodology research (referring to Achtenhagen, Winter, Nickolaus), but also on “(...) professional morale, the internal management of tasks, the ability to cooperate, the gender dependencies of career orientation, the habituation of professional experience and the question of reproducing learning interests over the course of life” (Harney 2020, 646). A variety of theories and research approaches are applied in this context, which means that a systemisation of this kind possesses only limited capacity to bring light to the darkness, as the Harney makes clear at another point: “The epistemic (foundational) premises of the subject-specific orientation towards structures of the psyche/the person/the learner (psychology, didactics), collectivity (sociology), regulated exchange (institutional economics), which are presupposed in the respective research and theoretical language, cannot be transferred to each other and instead divide VET research into complementary perspectives” (Harney 2020, 640). In places, though, these different perspectives address the individual levels of learning and curriculum development or the interaction between institutions.

Instead, this article adheres initially to the Bronfenbrenner model outlined above, which Rützel drew on in 1997 to conduct research into workplace-based learning (Rützel/Schapfel 1997b) and which was also used in the theoretical conceptualisation of commercial activities (refer to Figure 2). The model draws attention to the interdependence between the levels. This does not mean that researchers must engage in all areas or that they can or even want to due to the division of labour (Büchter/Eckelt 2022). However, when analysing VET, withdrawing and restricting research to one’s own origins in one of the scientific disciplines as cited by Harney would be tantamount to voluntarily accepting partial blindness. Similarly, focussing research on a single area of VET harbours the risk of overlooking the interdependencies and comes with a distinct susceptibility to mercurial trend topics, such as ‘digitalisation’, ‘workplace-based learning’, ‘skills assessment’, ‘sustainability’, ‘education in democracy’, ‘gender equality’ or ‘internationalisation’ etc. whose origin, relevance and justification is no longer (or can no longer be) made the subject of critical reflection.

In the following, I will briefly refer to an article from 2015 on the classification of subject areas within VET in Bronfenbrenner's levels. However, unlike Kell (2013, 9), I will not distinguish between the economic and education system, school and company, workplace and learning place, pupils and trainees, as the focus at that time was on company training regulations and activities.

|

Levels |

Object/actor |

Context |

Target orientation |

|

Macro-level |

Society/ state(s) |

Global market situation, political objectives, legal framework, national and international policy |

Prosperity, environment, employment |

|

Exo-level |

Education and |

Economic and education policy, |

Fulfilment of qualification requirements, functional division of labour |

|

Meso-level |

Companies |

Task assignments, organisational conditions |

Profit, retention, diversity management, sustainability, internationali-sation |

|

Micro-level |

Individual |

Activities |

Function-based and personal goals |

Figure 2: Socio-ecological levels and contexts of vocational qualifications and activities (Brötz/Kaiser 2015, 56)

3.1 Macro-level: Society (and its history), culture and international politics

Vocational education and training is embedded in a society whose respective form in a country or continent can only be grasped in its historical context (Kaiser 2020). Although Bronfenbrenner’s model was assigned another dimension of chronology in the sense of the individual life course (Bronfenbrenner 1986), it makes sense at this level to pay particular attention to the socio-historical and technical-historical dimension as chronology (cf. the historical-comparative VET research by Harney in the previous section). The economic structural factors and values shared across cultures or even geological and climatic conditions all impact prevailing structures in the individual countries and regions (Hjelm-Madsen/Kalisch 2022). Aside from the varying significance of economic sectors and international interdependencies, they also effect the acceptance of economic or welfare state goals, the development of collective or even clan economy (Baidoo et al. 2020) or meritocratic structures with the accompanying social inequalities and power structures both with and without socially regulated participation structures (Bertelsmann Stiftung 2022).

Bonoli and Gonon recently used the example of Switzerland to demonstrate how objectives of VET have changed over the course of history (Bonoli/Gonon 2022). Heikkinen had done the same for Finland a few years earlier, which illustrates how the development of VET also changes the social structure of society. An attempt that “[...] relates the sociologising macro-explanations and psychologising micro-examinations to the historical and cultural meanings of the totality of life of society and individuals” (Heikkinen 1996, 116). Increasingly coinciding with these chronological and spatial factors are others that result from supranational alliances (European Union) and international organisations and their reports (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, International Labour Organization, International Monetary Fund, World Trade Organization, World Bank, United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation), which exert considerable influence on national education and economic policy (Allais 2017; Moutsios 2009; Raffe 2012). Naturally, climate challenges (IPCC 2022), pandemic scenarios, technological progress (Zuleger 1988), changing work organisations (Ohno 1993) or the influences of the global market (Wagner 1987; Lutz 2007) cannot be ignored either in a consideration of VET.

3.2 Exo-level: National education and economic systems including politics

At the level of national education and economic systems, the framework conditions outlined above are reflected in the design of participation and governance structures (Iversen/Stephens 2008; Trampusch 2012; Bosch et al. 2007) in their institutional forms (Herkner 2003; BIBB 2010). The various structures of VET systems can be identified here in an international comparison (Greinert 2004), along with the different structures and traditions in sectors and occupations (Haipeter 2011). These aspects explain the heterogeneity of VET systems within a country (Friese 2018; Reinisch 2011; Nilsson 2008). Finally, there are also differences with regard to the influence of international regulations on vocational educational and training, which also possess significance for national standards, especially in logistics (Saniter 2012).

Furthermore, the consequences of national VET policy, with its effects on subsystems within the discipline (vocational orientation, vocational preparation, training, further training and continuing education), come into focus here, as evidenced by the historical reconstruction of the system of support for disadvantaged persons in Germany (Heissler/Lippegaus 2020) or in the transformation of continuing education in Europe (Singh/Schmidt-Lauff/Ehlers 2022). Schütte, who has analysed the history of vocational training law, makes clear that investigating these framework conditions is highly significant to the subject and hence the academic discipline: “Governance and regulation of the VET system require state intervention not merely due to its relevance for economic and labour market policy, but also because of its traditional socio-political engagement and the constitutional mandate to ensure equitable living conditions within the community” (Schütte 2012, 478).

Although there are an increasing number of studies on the evaluation of VET policy (Stockmann/Ertl 2021) and on the interaction between policy and VET research (Büchter/Eckelt 2022; Kaiser 2020; Kell 2015), there remains a paucity of intensive research into the international framework conditions as well as the changing values and political strategies (Allais 2017).

Moreover, public discourse and VET research rarely focus on VET policy in the narrower sense, which is reflected in the equal representation on committees, from the Board of the Federal Institute for Vocational Education and Training (BIBB) to the state committees for VET to the examination boards at the chambers and those involved in the creation of examination tasks (Busemeyer 2009; Eckelt et al. 2022). This applies all the more to an actual appraisal of participation and the safeguarding of rights (Kaiser/Kaup-Gottschalck/Labusch 2018).

The transformation of governance into a more evidence-based VET policy – now known as a ‘large-scale assessment – draws also on a level model that is comparable to the one presented here, which is based on Bronfenbrenner (Achtenhagen/Baethge 2007, 67) and on skills research (Achtenhagen 1996) that already extends to the following individual profession and company level.

3.3 Meso-level: Individual professions, professional groups and the curricular field of action

Since VET research also accompanies and helps in the curricular development of skills profiles, the consideration of the respective activity contexts of professions and the resulting requirements that must be developed for VET are key subjects for regulation-based VET research and development (Frank 2012). In 2013, Brötz and Schwarz clarified the mandate for regulation-based research, development and counselling placed in this regard as follows: “the development of job profiles and qualification requirements, the investigation of how professions are structured, tailored and classified, the implementation of regulations in companies, vocational schools and in examinations, the consideration of international requirements and the development of training and employment with regard to the usefulness of vocationally acquired qualifications” (Brötz/Schwarz 2013, 22).

In regard to research into skill needs, BIBB regularly cooperates with the Institute for Employment Research of the Federal Employment Agency (IAB) to publish skill needs forecasts, including a recent one that considers socio-ecological change and breaks it down into skills and professional areas (Wolter et al. 2023). The monitoring of changing requirements for specific industries or professions tends to focus on technical sectors (Becker/Spöttl 2014) or is produced in preparation for the emergence of new professions (Krämer/Bauer/Schraaf 2010). Although systematic analysis of professional groups brings their specific characteristics to light, it remains quite rare (Brötz/Kaiser 2015; Friese 2018).

The majority of work on skills research over recent decades has focused on the meso-level, producing individual professional studies and in some cases modelling only partial competences and yielding a rather sobering assessment of their effectiveness. Even Nickolaus, a dyed-in-the-wool skills researcher, writes: “With the exception of individual professions that have been the subject of very considerable research – mechatronics technician for motor vehicles, for instance – the domain models and available instruments continue to possess limited suitability to address the entire spectrum of requirements for professional work. Substantial and largely ignored deficits continue to exist, not least in the industrial-technical field, including in relation to motor skills and abilities. [...] Connections between personal, social and professional competences have received little research thus far” (Nickolaus 2017, 275).

Individual company structures must also be considered at the meso-level in regard to vertical integration and corresponding skills requirements or the co-determination structures that exist there. In most cases, for instance, works and staff councils must be involved in pending decisions about vocational training and hence, if they choose to do so, exert very considerable influence on in-company training (Berger 2012). But these topics are often omitted entirely in relevant literature (Breisig 2016), and the academic discipline barely addresses the issue of their effects on participation levels for in-company training (Berger/Eberhardt 2019).

Also of relevance are the analysis and consideration of action situations and framework conditions in vocational schools, be it their spatial and technical circumstances or those relating to school organisation and personnel management. To avoid elaborating on this field using related studies and writings, reference is made at this point only to a publication by Jörg-Peter Pahl (2014). Research approaches for school curricula also exist that focus on collaborative forms of development (Naeve-Stoß et al. 2019)

3.4 Micro-level: Work, teaching, interaction and personality

People act (including cognitive action) in the practice of their professions at the micro-level: they install, assemble, program, sell, negotiate, advise and produce, design, research, sum up, calculate, write or teach. Here, the specific requirements of a particular activity can be indicated based on the changes in technological possibilities (Piwek/Adamek/Schröter 2018), or activities can be analysed with regard to their impacts on health and personality (Hacker 2021). To this end, specific workplace observations can be acquired to make visible the complexity and regulatory requirements of individual sub-activities and, if necessary, to ensure they are learnable or to optimise their design (Schnauder 1997; Krell 2020).

This level includes the actual learning and teaching activities within VET (Besser et al. 2022). It is here that curricular plans are transposed into the reality of interpersonal interaction. Media – including how language is used in teaching (Efing 2013) – are applied just as much as models of interpersonal communication and interaction (Schapfel 1997). Profound microdidactic approaches to lesson planning in business didactics (Klusmeyer/Söll 2021) and actual course descriptions (Bartenschlage/Schönbeck 2013; Riehle 2015) are found here as well.

All the superordinate levels and the aspects outlined above exert influence on this level and, depending on the consideration and emphasis of the aforementioned framework conditions and their associated theories and concepts, shape the respective didactic approaches. This may be through a stronger focus on the ability to solve work-related problems, or by considering sustainability, democratic competence, interculturality, health, labour law, biographical reflexivity or professional identity etc. At the same time, the persons acting at these levels and in the relevant institutions are themselves shaped by the contexts of their everyday work and the associated socialisation and framework conditions (Schapfel-Kaiser 2007).

For example, the individual processes of embarking on vocational or academic education and the associated career trajectories – including how the persons concerned cope with the transitional situations – are located on this level and are shaped by the design of the specific workplaces, departmental cultures and individual management, behavioural and response patterns of the people working there (cf. Herzberg 2004 as an example).

3.5 Interdependence between the levels

Overlapping areas also become apparent if the levels are viewed as a tool to distinguish between topics within vocational training and education research. Hence, the subject of profession and vocation extends across the micro-, meso- and exo-levels, as educational and economic policy decisions are made to assign professions to academic or vocational training pathways are made also at the exo-level and thus may or may not involve economic policy actors in the curricular design, for instance in the reorganisation of nursing professions in contrast to the reorganisation of dual curriculum training professions or the high degree of autonomy that universities enjoy in the design of Bachelor’s degree programmes. At the same time, professions affect division of labour within companies and shape mentalities at a personal level (Haipeter 2011).

Similar interrelationships can be identified with regard to the world market, globalisation and labour policy, as well as the connection between climate change and curricular changes in job descriptions or, finally, the impact of technological progress on the design of lessons with digital media. Also of relevance is the issue of how inclusion and diversity – as specific elements within human rights objectives – impact selection mechanisms and communication in schools and companies.

4 Vocational education and training theory or theories and concepts for VET research?

The section begins by examining the theory and practice and then proceeds to the Frankfurt School’s critique of traditional theorising. Moreover, the problematic nature of thoughtlessly combining different research approaches based on varying underlying anthropological assumptions is noted as problematic, or must be disclosed transparently at least, as the approaches themselves build on different premises. The chapter concludes with a consideration of theories within VET research.

4.1 What is a theory?

The issue of what constitutes a theory or when it begins is without doubt one of the fundamental epistemological questions of scientific research and can only be addressed fleetingly at this point. The Greek origin of the word θεωρία (theōria) means ‘to look at’ and ‘to contemplate’. It follows, therefore, that theory is associated with holding still and taking no outward action (yet). This process of observing helps us to internalise what we perceive, compare it with current, already processed sensory impressions or science-based models, create connections and lend what we perceive its own image and structure (refer to Figures 2 and 3, which both draw on a tabular image form).

At the same time, this process inevitably inflicts violence on what is perceived, as the perceivers are initially compelled to follow this process of identification and ignore everything that is inconsistent with the theoretical model. The Frankfurt School critical theory reflects on this relationship of violence. In the words of Adorno in Negative Dialectics: “Unconsciously, so to speak, consciousness would have to immerse itself in the phenomena on which it takes a stand. [...] If the thought really yielded to the object, if its attention were on the object, not on its category, the very objects would start talking under the lingering eye” (Adorno 1966, 38). But this sets an almost unattainable goal, as the thought can only act with the language it knows, which, in order to be able to communicate with others, must itself refer to current understandings and cognitive patterns. It is among the reasons why theory, in a scientific context, sensibly seeks to ensure that views and abstractions of the observed practice can be communicated and shared, along with the methods and theories used for this purpose. This discourse is a valuable corrective that can be used to communicate and compare experiences and findings perceived and presented by others. At the same time, we remain aware that this communication process is shaped by career interests, citation cartels and, not least, the commercial interests of transnational corporations (Bhatnagar 2021).[3]

Let us adopt as a guide the conceptual pair of theory and practice on which educational science is based, as applied by Benner in 1980. Practice is perceived to mean two things here. First of all there is the existing world with all its laws, which provides space for practical action. This is joined by human action, which, as practice, relates to this existing world. So an interrelationship between human beings and the existing world is established in this practice. Human beings shape and are simultaneously shaped by the latter – especially through pedagogical action – which Benner also places in the dichotomy between individuals and society. “Educational practice is determined not only by the personal influence that educators exert and the individual participation of adolescents, but is inevitably exposed to social influences that do not easily satisfy the two principles developed thus far” (Benner 1980, 492). In his view, successful education is predicated upon the availability of a pedagogical theory; it is what enables purposeful action in a pedagogical context and is shaped by the social situation (refer to Figure 3).

|

Individual side of educational practice |

Social side of educational practice |

|

|

(A) Developmental theory |

(2) Encouragement to be active |

(3) Transformation of social determination into pedagogical determination |

|

(B) Educational theory |

(1) Educability as the human determinability for freedom |

(4) Concentration of all practices on the common task of humanity |

|

(C) Theory of pedagogical institutions |

(1)/(2): (3)/(4) |

|

Figure 3: Table of principles for the critique and foundation of pedagogical practice and educational theory formation (Benner 1980, 494)

Although the tension between the objectives is perfectly clear to Benner, as evidenced by the citation above, he views pedagogy as dedicated primarily to education for the freedom and higher development of humanity, which is consistent with the classic objective of bourgeois pedagogy. It is already clear at this point that educational theory refers to an aspirational state, but one that is yet to be attained. However, legitimate it may be to criticise the anthropocentric view of 1980 from today’s perspective, it is clear nonetheless that pedagogical action depends on theory as a place of reflection.

4.2 The challenge posed by critical (educational) theory

Critical theory, or critical educational theory, highlights that what needs to be done (educationally) must build on reasoned judgement and not on objectives that are rooted in political or economic power (cf. Euler 2020, 29). A categorical contradiction is formulated in regard to practice in a society that is shaped by the form of production – with the associated values and interests on the one hand, and the goals of emancipatory pedagogy on the other – which accuses bourgeois educational theory of naivety. “This bourgeois theory of the efficacy of enlightening reason – which at its heart will be a thoroughly pedagogical theory – must always assume that human practice is, in its inception, both moral and rational. All that remains is to realise it fully in order to arrive at a consciously moral practice” (Schmied-Korwazik 1980, 503). Instead, however, self-critical historical reflection in pedagogy and VET must accept that, in the context of the emerging Protestant religion, it can be perceived not least as a “basic bourgeois solution to the problem of mass morality” (Koneffke 1994, 151) and is hence entangled in a fraught relationship between liberation and authoritarianism (Heydorn 1970; Kaiser 2016).

This makes clear that although theory can be perceived as a view of practice – in VET especially (Schapfel-Kaiser 1998; Reinke 2019) – it must also include reflection on how it is connected to prevailing practice in each case and the personal background of the researcher. These aspects must be considered in order to establish transparency and transcend predetermined generalities in the interests of emancipation. Personal and social backgrounds place unconscious preconceptions in the cradle of the observer and can only be broken down and expanded through consciousness, deliberate and open confrontation with different traditions of thought and models. In doing so, they provide the opportunity to acquire a perception/theory that is appropriate to the subject. Aware of its entanglement with the historical and regional world, this realisation can only liberate science to a limited extent because “...however poorly the division of labour may function under the capitalist mode of production, its branches, science included, cannot be viewed as independent and autonomous. They are individuations of the ways and means in which society engages with nature and preserves its given form, moments in the social production process, however productive or otherwise they happen to be in a literal sense” (Horkheimer 1937, 253). With these words, Horkheimer points out that science and theory must be perceived as part of practice and can therefore never be objective. All of our mindsets are shaped by this prevailing societal rationality and are called upon to adopt a critical stance to this practical reference. This does not mean that scientific methods which apply various procedures to subject themselves to critical testing (validity, reliability, etc.) and strive for objectivity do not exist. But the very question of what is selected as the subject of research will follow the money. This in itself is inseparably linked to political decisions and is, furthermore, the product of social discourse and possibly strategic decisions by researchers (Dobischat/Münk 2019).

Vocational education and training theory and related concept developments must hence be aware of this entrenchment if they wish to grasp more than mere shadows of reality or end up tilting at windmills. Given this background, with the entanglement in practice and the knowledge of how one’s own research is historically connected, it is also important to reflect on the ideological foundations of theories (Mollenhauer 1983, Kipp/Miller-Kipp 1994).

4.3 On the combinability of theories that build on different anthropological assumptions

Theories and their associated world views are generally linked to a certain image of humankind and a philosophical tradition, without these links always becoming explicit and without the practitioners of the theories and concepts always being aware of their existence. This prompted Meinefeld to make clear in 1995 that he wishes to add an epistemological element to the contrast between explaining and understanding: “It is necessary to warn against the illusion that the investigation of epistemological preconditions has fashioned a space for research that is free of presuppositions. Even empirical research on the process of cognition is rooted in philosophical-theoretical assumptions that shape its results in a certain way. While there is no escaping this interrelationship between presupposition and observation, it can still be made fruitful if we become aware that experience and interpretation are interrelated” (Meinefeld 1995, 24). Hilbert Meyer distilled this insight in a simplified illustration of didactic theories and teaching methods in his well-known “didactic maps” (in Jank/Meyer 1991 as an appendix).

On the one hand, the illustration attempts to show the connections between theoretical developments and should be viewed historically from top to bottom. On the other, it can also be read from left to right as a chart of the anthropological foundations from Marx to Comte, so dialectical materialism to behaviourism, and their associated political currents. Other educational theories refer back to these theoretical foundations and proceed to develop various forms of teaching research. The result is a pictorial attempt to trace didactic approaches and applied research back to their more abstract sources.

The fact that the didactic landscape and research methods have continued to evolve is true of course. But it is equally clear that the call for a return to the underlying theories as proposed in this article builds on an understanding that views theory formation and hence method development and empirical research as influenced by society and history and is therefore more likely to be traced back to the theoretical foundations arranged on the left. The alternative would be a strict delineation between empirical social research and, for example, the formation of sociological theories: “Social research that is wholly committed to empiricism can address the aforementioned problem of a mutual relationship between theory and empiricism in two ways: it can either hope to arrive at a theory based on pure empiricism itself [...] but it can also consciously renounce any theoretical objective and limit itself to the function of merely supplying data to the political administration. This is made particularly clear with the institutionalisation of empirical social research in the form of official statistics: From now on, with its assumed neutrality and fungibility, it will be regarded as ideally suited to take on the function of an administrative auxiliary science” (Weismann 1980, 370). The objective at this point is most certainly not to catch up with the debate on positivism in sociology, but to use theories of VET research to point out the connection between theoretical concepts and the associated anthropological assumptions (cf. the Beck-Zabeck controversy in business education, refer to Tafner 2015).

A combination of methods belonging to empirical-analytical teaching-learning research with action research is by no means impossible based on the approaches of cultural-historical theory.[4] But this does require consideration and critical reflection, for example when developing and especially when adopting elaborate item batteries from teaching-learning research. The same applies to the use of deductively structured interviews that are not designed to generate a narrative and a subsequent interpretation, e.g. on the basis of the documentary method or grounded theory. Criteria for the assessment and to measure the success of successful teaching might otherwise contradict each other very significantly in regard to their underlying values and goals, without this being made explicit. This is equally true of combining qualitative teaching research with quantitative methods. The harmonies of the "mixed scores" certainly deserve attention in an age in which method triangulation has acquired such popularity that it increasingly seems like a hallmark of pedagogical research (Kelle 2007).

This does not suggest that one-sided research would be beneficial and would certainly not encourage any process of playing off the different research traditions and approaches against each other. Instead it favours a reflected application and consideration of the scope and, where applicable, opposing positions on which they are based.

From a socio-political perspective, the origins can be perceived as counter-movements to social processes or appendages of hegemonic philosophical traditions and should encourage modesty and awareness of their limited scope. After all, they shape our perceptions and interpretations either consciously or unconsciously, as we encounter them in everyday social discourse.

4.4 Which theories exist within VET research?

It should have become sufficiently clear from the elaborations thus far that VET research and business education cannot merely adopt a single theory or concept if it wishes to perceive itself as a science that places the research subjects on the different levels of VET research. Even researchers that focus on one level alone need to remain aware that there are influences from other levels that they must bring to mind using theories and concepts, as their work would otherwise become overly limited or even influenced by unconscious preconceptions and might simply adopt the scientific understandings and methods used by their academic teachers.

We might now, in an analysis of the ‘necessary’ theories and concepts, proceed once more along the Bronfenbrenner levels we used before. Then we would recognise the predominance of sociological and political theories for the analysis at the top level and that the spectrum ranges from structural-functionalist considerations, system theories and economic models to approaches within class analysis (Avis 2018). Sociological or economic concepts will feature most largely of all, depending on the thematic focus. “VET is thus considered as a reproductive institution of national economies, or as development of human resources in the global competition between companies and national economies” (Heikkinen 2020, 372). In most cases they will be governance perspectives that analyse systems of rule as political arenas from top to bottom and rarely perceive the interaction between the emerging structures and the logics and mentalities developed therein – so the culture, in other words. They may also, due to their ahistorical viewpoint, be blind to the conceptual changes resulting from shifting values in their own society (cf. the critique by Deißinger 2001). Ultimately, the change in political goals from a focus on the welfare state to neoliberal goals – in the Scandinavian states for example – has precipitated a paradigm shift in research and not merely in the political logics within the analysis spheres. And so efficiency criteria, financialisation and privatisation have found their counterparts to accompany research in the paradigms inherent to individualistic concepts such as lifeworld, subject and gender etc. “The emphasis shifted towards subjectivities, everyday life and media, to identity formation, ethnicity and gender, and to critique of cultural hegemonies” (Heikkinen 2021, 365).

However, localising the theories on the different levels appears only to make limited sense as the effects of politics and mentality, of practice and theory, are known to intermingle. Among the consequences of this is that, instead of identifying the cause for inadequate inclusion in an overarching meritocratic performance system, the socio-political issue of accountability for how successfully an individual copes with life – which is inherently linked to marketisation – is transferred to the domain of socio-educational support for disadvantaged persons or to the responsibility of the young people themselves. This is observable, for example, in the history of support for disadvantaged people and the associated funding policy by the Federal Employment Agency and the funding programmes initiated by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research in Germany (Koch 2008). In this way, young people who are disadvantaged by society become “young people who are insufficiently mature for education”, perpetuating their segregation in special programmes instead of attaining inclusion. “Each support programme should be accessible to all trainees and available as part of their regular VET. With regard to individual learning needs, this would introduce greater flexibility to the curricula of VET, and all training and education facilities would have to guarantee individual teaching-learning arrangements” (Heisler/Lippegaus 2020, 249)

Listing all the relevant – meaning received – theories reflected in the studies mentioned at the various levels in section 3 would exceed the scope of this article. Instead, the following will embark on a different path of presenting an orientation model for VET research that also includes the ecological perspective and the human connection to nature and is based on an ethical stance.[5]

5 A simple orientation model: Bringing personality – job requirements – community – world into balance

The premise of this article to provide information on how VET theories can contribute to acquiring multidimensional insight and hence prevent us from tilting at windmills, was approached with reflections on the subject matter of VET and its theories. This was only possible based on example, as the potential achievements of each theory would require an in-depth investigation that would fill an entire book, as we find in text- and handbooks (Lange et al. 2001; Arnold/Gonon/Müller 2015).

To sum up, it is reasonable to assert: a universally shared theory of VET does not exist.

- Vocational education and training research is shaped by value-based decisions

- individually at the direct action level and

- politically at the structural level

- These decisions are influenced by

- historical and cultural,

- power-structural, regional and

- technological conditions

A theoretical model must capture the interdependence between the subject areas. This article will therefore draw on a model of theme-centred interaction that was originally developed in the 1990s in research work for VET. The tense relationship between learning, in the meaning of emancipative education on the one hand, and work in an economic system that is geared towards marketability on the other, was made accessible for analysis by adopting a ‘critical-subject-oriented view’ of VET research (Rützel/Schapfel 1997a). Associated with this was a perception that, building on the historical and collective experience of National Socialism in Germany, sought to identify the goals of emancipative education that embraces empowerment and the possibilities for emancipating the individual in all pedagogical design processes and consequently also in VET. The aim was to uncover which current ideas, concepts, structures and practices in vocational and business training and education act as barriers to aspirations for an emancipatory ideal and its realisation. Overcoming these barriers would then become the purpose of pedagogy (Schapfel 1996).[6]

Adopting this approach enables the design of processes that integrate socio-analytical aspects into vocational education and training. By doing so, it enables not only biographical self-reflection in regard to qualifications (Schapfel-Kaiser 1998), but also shines a light on the contradictions inherent to the form of production in a democratic society with progressive marketisation (Kaiser/Ketschau 2019), which Lempert, Büchter, Kutscha and Ehrke, among others, have repeatedly addressed. Critical educational theory hence becomes a theoretical approach that, taking sociological theories into account, broadens the view of society as a whole and at the same time addresses the consequences for vocational education and training, whose aim is not to adapt to the prevailing circumstances and rather to enable learners to shape their future and that of the world in a meaningful way on an ethical basis. In more current contexts, this would address the danger inherent to an overly narrow discourse on the integration of sustainable goals into VET (Kaiser 2023; Euler 2022). It would also deal with the historical subservience that still resides within vocational education and training (Kaiser 2021) and encourages adaptation, as resistance would harbour the risk of exclusion (Kaiser/Ketschau 2019).

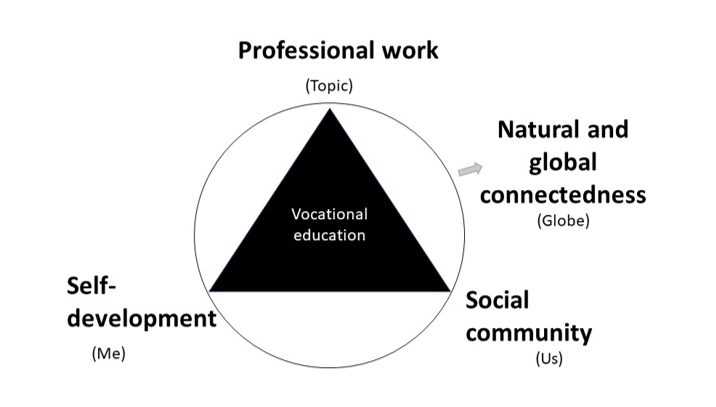

Figure 4: Orientation model of criteria-structural VET theory

Figure 4: Orientation model of criteria-structural VET theory

Building on the preliminary considerations outlined above, the preceding orientation model (Figure 4), which adapts the TCI model in its basic structure and is characterised by subject, Me, Us and the surrounding Globe (Schapfel-Kaiser 1997), has proven valuable. Direct references to the developmental tasks that young people face (Quenzel/Hurrelmann 2022) would become clear in an alternative presentation form. Put succinctly, they are: economic self-sufficiency (professional work), partner and family role (social community), individual regeneration (personal growth) and political participation (nature and global influences) and offer equally helpful starting points for vocational education and training. The Bronfenbrenner levels outlined earlier in this article can be brought together here in a simpler image, which still indicates that topics are not always located on separate levels or hierarchies and are instead inextricably linked.

(1) Professional work could be placed at the top in regard to the subject of vocational education and training. It is the guiding theme, as its purpose is to enable precisely this (cf. Bonoli and Gonon in this special issue). This is why studies within labour, occupational, cultural and social sciences are such necessary factors in VET research, as they help to identify the aspects that shape the preferred profession or professionalism in this field of activity or sector. Only then is it possible to identify core competences for the professions, which then become the starting point for projects, for example in the didactic design of learning fields (Jepsen 2022). The skills and knowledge that need to be acquired and the cultural attributes of a profession can all be visualised here. These analysed activities must be placed in relation to their action contexts and historical genesis (Brötz/Kaiser 2015) if their entire educational content is to be made accessible to learners. The German word ‘Banause’ has the figurative meaning of ‘philistine’. Adopted from the Greek, it means ‘the one who works at the stove’. It was a pejorative term for craftsmen and indicated that they were forced to earn a living with physical labour and were therefore presented from devoting themselves to other cultural goods and to building the city (Kutscha 2008). In fact, participation in social power and political organisation, the availability of economic resources to shape individual lives and the extent of available time – in short, status – are still predestined by the chosen profession or professionally organised gainful employment (Hoffmeyer-Zlotnik/Geis 2003).

(2) This brings us to the issue that has been labelled here as personal growth or elsewhere as subject orientation (Schapfel 1996). This is an area which vocational education and training is intended to promote or which is hindered when reduced to merely completing a small range of tasks (Beck/Brater/Daheim 1980). Personal growth as a goal of vocational education and training demands that vocational learning should be geared not only towards practical induction in the context of gainful employment (Heinrich/Wuttke/Kögler 2022). Instead and additionally, it should raise the simple question of how an individual learner arrived at their decision to embark on a particular career, which associations he or she will attach to it going forward and how he or she intends to organise these tasks (Kalisch/Kley/Prill 2020). Doing so provides access to individual moral reflection and the discovery of personal creative power – the starting points for maturity and emancipation (Thole 2021). Given that personal growth can only take place within a context of successful self-preservation, aspects of physical regeneration, health and mindfulness must also be integrated into VET, not least to safeguard access to the connection between people and nature (Vogel 2011). Obtaining even sketchy access to the historical context of a person’s decision to embark on a particular profession will enable them to identify with a sub-area within the social division of labour and throw open the wider societal context of meaning. This is because it allows them to grasp why and when the profession or industry came into being and how work in this field is or was intended to make a meaningful contribution to society (Reinisch 2011).

(3) We now come to the social community in which the person acting in a professional capacity within the company becomes integrated and which he or she helps to shape. Just like the family and peer groups in which young adults are integrated, trainees shape social communities in their living environment by means of their actions or inactions as well as their methods of communication and interaction and are socialised by the cultures prevailing there (Wenger 1998; Schapfel-Kaiser 2007). This integration into the social community of employees or workers can transcend the boundaries of one’s own company through trade union involvement and lead to an awareness of a greater connection between oneself and others (Haunss 2001). The same applies away from work to engagement in social movements, clubs and associations etc. Interest in music and hobbies also provide access to social communities as additional building blocks for social participation that can be thoughtfully integrated into vocational education and training. In a vocational education and training programme that is geared towards lifeworlds, they then become learning opportunities for personal development and also enrich the process of joint learning. This creates occasions for reflection on social behaviour, with a view to the question of communities in which people feel or do not feel comfortable and why this may be the case, but also which political goals are consistent and how interests can be asserted in practice (Zurstrassen 2013).

(4) The connection to the physical, physical foundations of one's own existence – which were mentioned already under personal growth – refers to the prevailing conditions in which we all live. It is therefore imperative to recognise the significance of nature and global connectedness for vocational education and training – both with regard to designing the content of learning situations and curricula as well as in the area of research (Vogel 2011). This is also linked to the social community mentioned above, which extends beyond the immediate circle of acquaintances and opens the door to society, culture and politics. The role of influential factors at national and international level has already been noted for the area of research. With regard to the learning objects in vocational education and training, the current discourse on sustainability and how it is embedded within the legal requirements offers an excellent basis to expand the view beyond the immediate remit of a workplace and the scope of a company’s action (Kaiser/Schwarz 2021). The demand placed in VET to create access to the world, or in the words of Kerschensteiner (1904), to serve as a “gateway to human formation”, can only be made possible by integrating processes from the entire world. Contextualities of professional actions can be used as a basis to recognise complex interrelationships between global events. And even if they are not addressed in detail by the curriculum, it is precisely these aspects that teachers must make accessible in a manner that accommodates the possibilities and interests of learners (Lisop/Huisinga 1994).

The co-determination and participation of employees in company decision-making processes – along the lines of furthering democracy within the company – depend on the formation of well-founded opinions that extend beyond a person’s own area of work and the company horizon. Critical appraisal of value-orientated decisions must be encouraged and directed against any division that distinguishes between what is actually sensible and what, for whatever reason, appears operationally justified, and between those who are vested with the power to decide and others who are merely required to follow instructions (Fischer 1998). German history and the events in Fukushima taught us the devastating consequences that this can have (Langemeyer 2019).

The brief remarks on the points of orientation in Figure 6 clearly show the extent to which vocational education and training can and should be organised to facilitate contextual understanding of one's own actions. In doing so, people become empowered to take responsibility for their professional activities, be it in relation to personal preservation, the future of the world or the resolution of specific technical or interpersonal problems. None of this is intended to devalue research that devotes itself to a particular field, as this also advances the state of research and provides in-depth insights into subject areas, without always referring to the wider context. The sole purposes were to highlight the risk of partial blindness and point to potential solutions in an increasingly complex world.

References

Achtenhagen, F. (1996): Entwicklung und Evaluation ökonomischer Kompetenz mit Hilfe handlungsorientierter Verfahren am Beispiel der Ausbildung zum Industriekaufmann/zur Industriekauffrau. In: Seyd, W./Witt, R. (Hrsg.): Situation – Handlung – Persönlichkeit. Festschrift für Lothar Reetz. Hamburg, 137-147.

Achtenhagen, F./Baethge, M. (2007): Kompetenzdiagnostik als Large-Scale-Assessment im Bereich der beruflichen Aus- und Weiterbildung. In: Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft, Sonderheft 8, 51-70.

Adorno, T. W. (1966): Negative Dialektik. Frankfurt.

Allais, S. (2017): Labour market outcomes of NQFs. What is known about what they can and can’t do? In: Kaiser, F./Krugmann, S. (Eds.): Social Dimension and Participation in Vocational Education and Training. Proceedings of the 2nd conference “Crossing Boundaries in VET”. Rostock, 9-20.

Arnold, R./Gonon, P./Müller, H.-J. (Hrsg.) (2015): Einführung in die Berufspädagogik (2.Aufl.). Opladen.

Avis, J. (2018): The re-composition of class relations: Neo-liberalism, precariousness, youth and education. In: Smyth, J./Simmons, R. (Eds.): Education and Working Class Youth. London, 131-153.

Baidoo, M. K./Tachie-Menson, A./Arthur, N. A. P./Asante, E. A. (2020): Understanding informal jewellery apprenticeship in Ghana: Nature, processes and challenges. In: IJRVET, 7, H. 1, 45-66. Online: https://doi.org/10.13152/IJRVET.7.1.3 (13.03.2023).

Beck, U./Brater, M./Daheim, H. (1980): Soziologie der Arbeit und Berufe. Grundlagen, Problemfelder und Forschungsergebnisse. Reinbeck.

Becker, M./Spöttl, G. (2014): Berufswissenschaftliche Fallstudien und deren Beitrag zur Evaluation des Ausbildungsberufs Kfz-Servicemechaniker/-in. In: Severing, E./Weiß, R. (Hrsg.): Weiterentwicklung von Berufen – Herausforderungen für die Berufsbildungsforschung. Bonn, 99-116.

Benner, D. (1980): Das Theorie-Praxis-Problem in der Erziehungswissenschaft und die Frage nach Prinzipien pädagogischen Denkens und Handelns. In: ZfP, 26, H. 4, 485-498.

Berger, K. (2012): Betriebsräte und betriebliche Weiterbildung. In: WSI Mitteilungen, 65, H. 5, 358-364.

Berger, K./Eberhardt, C. (2019): Ausbildung und Mitbestimmung in klein- und mittelständischen Betrieben in Deutschland: Welchen Beitrag leisten Betriebsräte in Ausbildungsfragen? In: Gramlinger, F./Iller, C./Ostendorf, A./Schmid, K./Tafner, G. (Hrsg.): Bildung = Berufsbildung?! Bielefeld, 87-98. Online: https://doi.org/10.3278/6004660w087 (13.03.2023).

Bertelsmann Stiftung (Hrsg.) (2022): BTI 2022 Globale Ergebnisse – Abnehmende Resilienz. Gütersloh. Online: https://www.bertelsmann-stiftung.de/fileadmin/files/BSt/Publikationen/GrauePublikationen/BTI_2022_Globale_Ergebnisse_DE.pdf (02.03.2023).

Besser, L./Traum. A./Kaiser, F./Rau, R. (2022): Observe-ask-analyze. TAG-MA, a new condition-related job analysis method to describe the work of VET teachers. In: Herrera, L./Teräs, M./Gougoulakis, P./Kontio, J. (Eds.): Learning, Teaching and Policy Making in VET. Stockholm, 127-157. Online: https://www.su.se/polopoly_fs/1.644489.1674729137!/menu/standard/file/Emergent%20Vol%208-Inlaga-POD-Korr4-230109.pdf (14.04.2023).

BIBB (Bundesinstitut für Berufsbildung) (2010): 40 Jahre Bundesinstitut für Berufsbildung: 40 Jahre Forschen – Beraten – Zukunft gestalten. Bonn.

Bonoli, L./ Gonon, P. (2022): The evolution of VET systems as a combination of economic, social and educational aims. The case of Swiss VET. In: Hungarian Educational Research Journal, 12, H. 3, 1-12.

Bosch, G./Haipeter, P./Latniak, E./Lehndorff, S. (2007): Demontage oder Revitalisierung? Das deutsche Beschäftigungsmodell im Umbruch. In: Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie, 59, H. 2, 318-339.

Breisig, T. (2016): Personalentwicklung in mitbestimmungspolitischer Perspektive. In: Zeitschrift für Personalforschung, 7, H. 1, 7-24. Online: https://doi.org/10.1177/239700229300700102 (23.12.2021).

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1981): Die Ökologie der menschlichen Entwicklung (2. Aufl.). Stuttgart.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1986): Recent Advances in Research on the Ecology of Human Development. In: Silbereisen, R. K./Eyferth, K./Rudinger, G. (Eds.): Development as Action in Context. Berlin.

Brötz, R./Kaiser, F. (2015): Kaufmännische Berufe – Charakteristik, Vielfalt und Perspektiven. Bielefeld.

Brötz, R./Schwarz, H. (2013): Standards in der Berufsbildung durch Forschung und Praxisdialog. In: BWP, 42, H. 2, 20-23.

Büchter, K./Eckelt, M. (2022): Berufs- und Wirtschaftspädagogik und Berufsbildungspolitik – eine Verhältnisfrage. In: Bohlinger, S./Scheiermann, G./Schmidt, C. (Hrsg.): Berufsbildung, Beruf und Arbeit im gesellschaftlichen Wandel. Zukünfte beruflicher Bildung im 21 Jhdt. Wiesbaden, 107-125. Online: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-37897-4_8 (09.11.2022).

Busemeyer, M. R. (2009): Die Sozialpartner und der Wandel in der Politik der beruflichen Bildung seit 1970. In: Industrielle Beziehungen, 16, H. 3, 273-294.

Çaģlar, G. (2010): Gender and Economics. Feministische Kritik der politischen Ökonomie. Wiesbaden.

Cohn, R. C. (1992): Von der Psychoanalyse zur themenzentrierten Interaktion. Von der Behandlung einzelner zu einer Pädagogik für alle. Stuttgart.

Deißinger, T. (2001): Zum Problem der historisch-kulturellen Bedingtheit von Berufsbildungssystemen – Gibt es eine „Vorbildfunktion“ des deutschen Dualen Systems im europäischen Kontext? In: Deißinger, T. (Hrsg.): Berufliche Bildung zwischen nationaler Tradition und globaler Entwicklung. Baden-Baden, 11-44.

Dobischat, R./Münk, D. (2019): Forschungssteuerung durch öffentliche Programmförderung. Kritische Anmerkungen zu ihrer Wirksamkeit und ihren (nicht intendierten) Effekten. In: Berufsbildung, 73, H. 178, 6-8.

Eckelt, M./Ketschau, T. J./Klassen, J./Schauer, J./Schmees, J. K./Steib, C. (2022): Berufsbildungspolitik: Strukturen – Krise – Perspektiven. Bielefeld.

Efing, C. (2013): „Wir brauchen keine Diskussionsmechaniker!“ Zum sprachlichen Handeln der Industriemechaniker/-innen in der Ausbildung. In: Lernen und Lehren, 28, H. 2, 56-63.

Epp, A. (2018): Das ökosystemische Entwicklungsmodell als theoretisches Sensibilisierungs- und Beratungsraster für empirische Phänomene. In: Forum: Qualitative Sozialforschung, 19, H. 1, Art. 1.

Euler, P. (2020): Dennoch: Pädagogik. Gesellschafts- und Selbstkritik als Bedingung einer in Bildung begründeten Pädagogik. In: Leseräume. Zeitschrift für Literalität in Schule und Forschung, 7, H. 6, 27-43.

Euler, P. (2022): Nicht-Nachhaltige Entwicklung. Das Konzept »Bildung für nachhaltige Entwicklung« im Widerspruch von Systemmodernisierung und grundsätzlicher Systemtransformation. In: punktum – Zeitschrift für verbandliche Jugendarbeit in Hamburg, 2, 9-14.

Ferber, M./Nelson, J. (2003): Feminist Economics Today. Beyond Economic Man. Chicago.

Fischer, A. (1998): Wege zu einer nachhaltigen beruflichen Bildung. Bielefeld.

Frank, I. (2012): Die Entwicklung von Berufen im Rückblick. In: Frank, I./Walden, G. (Hrsg.): Analysen und Empfehlungen zur Festlegung der Dauer von Ausbildungsberufen. Bonn, 4-8. Online: https://www.bibb.de/dienst/publikationen/en/download/6893 (12.01.2023).

Friese, M. (2018): Berufliche und akademische Ausbildung für Care Berufe. Überblick und fachübergreifende Perspektiven der Professionalisierung. In: Friese, M. (Hrsg.): Reformprojekt Care. Professionalisierung der beruflichen und akademischen Ausbildung. Bielefeld, 17-44.

Greinert, W. D. (2004): European Vocational Training "Systems" – Some Thoughts on the Theoretical Context of Their Historical Development. In: European Journal: Vocational Training, 32, 18-25. Online: https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/files/32-en.pdf (15.12.2022).

Hacker, W. (2021): Psychische Regulation von Arbeitstätigkeiten 4.0. Zürich.

Haipeter, T. (2011): Kaufleute zwischen Angestelltenstatus und Dienstleistungsarbeit – eine soziologische Spurensuche. Bonn. Online: https://www.bibb.de/veroeffentlichungen/en/publication/download/6721 (09.08.2017).

Harney, K. (2020): Theorieansätze der Berufsbildung. In: Arnold, R./Lipsmeier, A./Rohs, M. (Hrsg.): Handbuch Berufsbildung. Wiesbaden, 639-650. Online: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-19312-6_49 (09.05.2022).

Haunss, S. (2001): Was in aller Welt ist „kollektive Identität“? Bemerkungen und Vorschläge zu Identität und kollektivem Handeln. In: Gewerkschaftliche Monatshefte, 52, H. 5, 258-267.

Heikkinen, A. (1996): Berufsbildung als Faktor des sozialen Wandels in Finnland. In: Greinert, W.-D./Harney, K./Pätzold, G. (Hrsg.): Berufsbildung und sozialer Wandel. 150 Jahre preußische Gewerbeordnung. Bielefeld, 115-135.

Heikkinen, A. (2021): Culture and VET – An Outdated Connection? In: Eigenmann, P./Gonon, P./Weil, M. (Eds.): Opening and Extending Vocational Education. Bern, 361-382.

Heinrichs, K./Wuttke, E./Kögler, K. (2022): Berufliche Identität, Identifikation und Beruflichkeit – Eine Verortung aus der Perspektive einer theoriegeleiteten empirischen Berufsbildungsforschung. In: bwp@ Berufs- und Wirtschaftspädagogik – online, 7, 1-28. Online: https://www.bwpat.de/profil7_minnameier/heinrichs_etal_profil7.pdf (18.06.2023).

Heisler, D./Lippegaus, P. (2020): Reparaturbetrieb, Inklusion und Fachkräftesicherung. Transformation der Benachteiligtenförderung in Deutschland. In: Kaiser, F./Götzl, M. (Hrsg.): Historische Berufsbildungsforschung. Detmold, 231-251. Online: https://shop.budrich.de/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/9783847418344.pdf (10.10.2022).

Herkner, V. (2003): Deutscher Ausschuß für Technisches Schulwesen. Untersuchungen unter besonderer Berücksichtigung metalltechnischer Berufe. Hamburg.

Herzberg, H. (2004): Biographie und Lernhabitus. Eine Studie im Rostocker Werftarbeitermilieu. Frankfurt.

Heydorn, H. J. (1970): Über den Widerspruch von Bildung und Herrschaft. Frankfurt.

Hjelm-Madsen, M./Kalsich, C. (2022): Regionale Disparitäten in der Berufsbildungsforschung: Deutungsmuster und Bewertungsansätze zwischen Vielfalt und Ungerechtigkeit. In: bwp@ Berufs- und Wirtschaftspädagogik – online, 42, 1-20. Online: https://www.bwpat.de/ausgabe42/hjelm-madsen_kalisch_bwpat42.pdf (30.06.2023).

Hoffmeyer-Zlotnik, J./Geis, A. (2003): Berufsklassifikation und Messung des beruflichen Status/Prestige. In: ZUMA Nachrichten, 27, H. 52, 125-138. Online: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-207823 (09.08.2023).

Horkheimer, M. (1937): Traditionelle und Kritische Theorie. In: Zeitschrift für Sozialforschung, 6, 245-251.

IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) (Eds.) (2022): Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press.

Jepsen, M. (2022): Arbeitsmarkt- und Berufsinformation als Datenbasis für eine verbesserte Abstimmung zwischen Bildung und Beschäftigung. Ein Verfahren zur Entwicklung beruflicher Curricula am Beispiel des Bereichs der Informations- und Kommunikationstechnologie. Frankfurt.

Kaiser, F. (2016): Berufliche Bildung und Emanzipation – Heydorns Impulse für eine kritische Berufsbildungstheorie sowie Stolpersteine aus eigener berufspädagogischer Sicht. In: Ragutt, F./Kaiser, F. (Hrsg.): Menschlichkeit der Bildung. Heydorns Bildungsphilosophie im Spannungsfeld von Subjekt, Arbeit und Beruf. Paderborn, 181-198.

Kaiser, F. (2020): Reflections on typologies of comparison studies and the necessity of cultural-historical views illustrated by the analysis of the Swedish vocational education system from abroad. In: Pilz, M./Li, J. (Hrsg.): Comparative Vocational Education Research, Internationale Berufsbildungsforschung. Wiesbaden, 259-274.

Kaiser, F. (2021): Berufliche Bildung ohne Ermächtigung zum Widerspruch ist Produktion von Untertanen. Zur kritischen Selbstreflexion im Kontext beruflicher Lehrkräftebildung. In: Marose, M./Schütze, K. (Hrsg.): Unter dem dünnen Firnis der Zivilisation. Erinnerungskulturen im Religionsunterunterricht an berufsbildenden Schulen und in der außerschulischen Bildung, Glaube – Wertebildung – Interreligiosität, Band 20. Münster, 135-150.

Kaiser, F. (2023): Berufliche Bildung als Befähigung zum Widerstand gegen eine nicht-nachhaltige Gegenwart. In: Berufsbildung, 197, 2-5.

Kaiser, F./Ketschau, T. (2019): Die Perspektive kritisch-emanzipatorischer Berufsbildungstheorie als Widerspruchsbestimmung von Emanzipation und Herrschaft. In: Wittmann, E./Frommberger, D./Ziegler, B. (Hrsg.): Jahrbuch der berufs- und wirtschaftspädagogischen Forschung 2019. Bielefeld, 13-29.

Kaiser, F./Keup-Gottschalck, M./Labusch, G. (2018): Fehler im System – Folgen automatisierter Prüfungsauswertung. In: BWP, 47, H. 2, 56-57.

Kaiser, F./Schwarz, H. (2021): Impulse für Nachhaltigkeit in der beruflichen Bildung? Kritische Reflexionen zur aktuellen Verankerung der Nachhaltigkeit in den Mindeststandards der Ausbildungsordnungen. In: Michaelis, C./Berding, F. (Hrsg.): Berufsbildung für nachhaltige Entwicklung. Umsetzungsbarrieren und interdisziplinäre Forschungsfragen. Bielefeld, 115-131.

Kalisch, C./Kley, S./Prill, T. (2020): Selbsterkundung und Förderung individueller Entscheidungen in der Beruflichen Orientierung: Neukonzeption des Potenzialanalyse-Ansatzes. In: Driesel-Lange, K./Weyland, U./Ziegler, B. (Hrsg.): Berufsorientierung in Bewegung. Themen, Erkenntnisse und Perspektiven. ZBW-Beiheft 30. Stuttgart, 155-168.

Kelle, U. (2007): Die Integration qualitativer und quantitativer Methoden in der empirischen Sozialforschung. Theoretische Grundlagen und methodologische Konzepte. Wiesbaden.

Kerschensteiner, G. (1966/1904): Berufs- oder Allgemeinbildung? In: Wehle, G. (Hrsg.): Georg Kerschensteiner. Berufsbildung und Berufsschule. Ausgewählte Pädagogische Schriften. Band 1. Paderborn, 89-104.

Iversen, T./Stephens, J. D. (2008): Partisan Politics, the Welfare State, and Three Worlds of Human Capital Formation. In: Comparative Political Studies 41, H. 4/5, 600-637.

Jank, W./Meyer, H. (1991): Didaktische Modelle (5. Aufl.). Berlin.

Kell, A. (2013): Produktionsschule – Übergangssystem – Lern-Arbeits-System: Berufsbildungswissenschaftliche Perspektiven. In: bwp@, Spezial 6, 1-34. Online: http://www.bwpat.de/ht2013/ws09/kell_ws09-ht2013.pdf (23.12.2021).

Kipp, M./Miller-Kipp, G. (1994): Kontinuierliche Karrieren – diskontinuierliches Denken? Entwicklungslinien der pädagogischen Wissenschaftsgeschichte am Beispiel der Berufs- und Wirtschaftspädagogik nach 1954. In: Zeitschrift für Pädagogik, 40, H. 5, 727-744.

Koch, M. (2008): Kritische Bestandsaufnahme der außerschulischen Berufsvorbereitung. In: Bojanowski, A./Mutschall, A./Meshoul, A. (Hrsg.): Überflüssig? Abgehängt? Produktionsschule: Eine Antwort für benachteiligte Jugendliche in den neuen Bundesländern. Münster, 47-68.

Koneffke, G. (1994): C. F. Bahrdts „Handbuch der Moral für den Bürgerstand“ (1789) im Konstitutionsprozeß der Pädagogik. In: Koneffke, G. (Hrsg.): Pädagogik im Übergang zur bürgerlichen Herrschaftsgesellschaft: Studien zur Sozialgeschichte und Philosophie der Bildung. Wetzlar, 137-173.

Krämer, H./Bauer, W./Schraaf, U. (2010): Strukturwandel in Medienberufen. Abschlussbericht. Bonn. Online: https://www.bibb.de/dienst/dapro/daprodocs/pdf/eb_42320.pdf (05.11.2022).

Krell, K.-M. (2020): Risikobetrachtung für den Asphaltaus- und -einbau im Grenzbereich zum fließenden Kraftfahrzeugverkehr unter Berücksichtigung der Standardarbeitsverfahren und Arbeitsmittel. Dresden.

Kutscha, G. (2008): Arbeit und Beruf – Konstitutive Momente der Beruflichkeit im evolutionsgeschichtlichen Rückblick auf die frühen Hochkulturen Mesopotamiens und Ägyptens und Aspekte aus berufsbildungstheoretischer Sicht. In: Zeitschrift für Berufs- und Wirtschaftspädagogik, 104, H. 3, 333-357.

Lange, U./Harney, K./Rahn, S./Stachowski, H. (2001): Studienbuch Theorien beruflicher Bildung. Bad Heilbrunn.

Langemeyer, I. (2019): Mindfulness and the psychodynamics in high-reliability-organizations: Critical-psychological considerations for a research on high-tech work. In: Annual Review of Critical Psychology, 16, 1237-1257.

Lisop, I./Huisinga, R. (1994): Arbeitsorientierte Exemplarik. Theorie und Praxis subjektbezogener Bildung. Frankfurt a. M.

Lutz, H. (2007): Vom Weltmarkt in den Privathaushalt: Die neuen Dienstmädchen im Zeitalter der Globalisierung. Opladen.

Meinefeld, W. (1995): Realität und Konstruktion: erkenntnistheoretische Grundlagen einer Methodologie der empirischen Sozialforschung. Opladen. Online: https://www.ssoar.info/ssoar/handle/document/1571 (20.03.2023).

Mollenhauer, K. (1983): Vergessene Zusammenhänge. Über Kultur und Erziehung. München.

Moutsios, S. (2009): International organisations and transnational education policy. In: Compare, 39, H. 4, 469-481.

Naeve-Stoß, N./Wenge, G./Büker, L. (2019): Lernfeldorientierte Curriculum- und Unterrichtsentwicklung in Kooperation von Berufsschule und Universität am Beispiel der Kaufleute im E-Commerce. In: Wilbers, K. (Hrsg.): Digitale Transformation kaufmännischer Bildung. Ausbildung in Industrie und Handel hinterfragt. Texte zur Wirtschaftspädagogik und Personalentwicklung. Band 23. Berlin, 267-290.

Nickolaus, R. (2017): Kompetenzmodellierungen in der beruflichen Bildung – eine Zwischenbilanz. In: Schlicht, J./Moschner, U. (Hrsg.): Berufliche Bildung an der Grenze zwischen Wirtschaft und Pädagogik. Wiesbaden, 255-281. Online: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-18548-0_14 (23.12.2021).

Nilsson, A. (2008): Vocational education and training in Sweden 1850-2008 – a brief presentation. In: Bulletin of Institute of Vocational and Technical Education, 5, 78-91. Online: http://lup.lub.lu.se/record/1502864 (08.10.2018).

Ohno, T. (1993): Das Toyota-Produktionssystem. Frankfurt a. M.

Pahl, J.-P. (2014): Berufsschule: Annäherungen an eine Theorie des Lernortes (3. Aufl.). Bielefeld.

Piwek, V./Adamek, J./Schröter, M. (2018): Betriebliche Qualifikationsanforderungen in Konstruktion und Fertigung beim Einsatz additiver Fertigungsverfahren. In: Lernen und Lehren, 33, H. 3, 98-102. Online: http://lernenundlehren.de/heft_dl/Heft_131.pdf (23.12.2021).

Quenzel, G./Hurrelmann, K. (2022): Lebensphase Jugend. Eine Einführung in die sozialwissenschaftliche Jugendforschung (14 Aufl.). Weinheim.