Über bwp@

bwp@ ... ist das Online-Fachjournal für alle an der Berufs- und Wirtschaftspädagogik Interessierten, die schnell, problemlos und kostenlos auf reviewte Inhalte und Diskussionen der Scientific Community zugreifen wollen.

bwp@ 39 - Dezember 2020

Berufliche Bildung in Europa – 20 Jahre nach Lissabon und am Ende von ET 2020. Entwicklungen und Herausforderungen zwischen supranationalen Strategien und nationalen Traditionen

Hrsg.: , , , &

French exceptionalism tested against the Lisbon strategy principles. The case of the Qualifications Framework implementation process

The present article focuses on the process of reform and establishment of the new French National Qualifications Framework. We describe some of the circumstances that led to its adoption in France in the context of the law of 5 September 2018 on the “freedom to choose one's professional future”. The process of adopting the new framework lasted ten years. The reason is to be found in national stakeholders’ regard for their VET system, which was seen as country-specific and hardly adaptable to European injunctions. As a national centre of expertise on qualifications, training and employment, Céreq had the opportunity to be involved in the process. This journey through the evolution of the French system shows that even if the European policy agenda (based on promoting mobility and guaranteeing comparability of qualifications) was not at the heart of the French reform process, it gradually entered into the debate, with references being made to it in official and working documents issued by national agencies. The final result was gradual alignment with the Lisbon principles, even though they were never the main drivers of reform.

1 European and national policies: a permanent interaction.

Did the Lisbon process have a direct impact on the reform of French public policy? Can the modernisation of the French qualifications system be described as a response to European policies or were these reforms driven by other factors? Can we really talk of a cause and effect relationship between European and French policies?

Providing definitive answers to these questions is a difficult task. A more realistic goal would be to examine a single public policy in which European and national discourses have coexisted for a long time, often conflicting with each other but at the same time influencing the reform process. The present article focuses on the process of reform and establishment of the new French National Qualifications Framework.

One of the main goals of the Lisbon Process was to allow European citizens “to move within the European labour market and to pursue genuine lifelong and lifewide learning”. Another major objective was to bring about an “increase of transparency of qualifications and lifelong learning national systems” (European Commission, 2006). To this extent one of the first concrete policy acts was the release in 2006 of the European Qualifications Framework and the subsequent referencing work that all EU member were called to undertake in order to make conceptual connections between the national qualifications systems and the overarching European scheme. This referencing work was often an opportunity for member states to rethink or reconsider the fundamentals of their training systems. In some cases, this revision was somewhat painful and met with considerable resistance, particularly in countries where training systems were still input-based, i.e. rooted in the transmission of theoretical knowledge, and not output-based, i.e. shaped by the competences to be acquired.

The Polish case could be taken as an example in this respect. The modernisation of the qualifications system in Poland was undertaken in response to European policies but also offered an opportunity to implement the Polish national policy on lifelong learning. The reform process introduced, for the first time in Poland, the learning outcomes approach as the primary reference concept for education policies. The new qualifications architecture based on learning outcomes was implemented in record time between 2008 and 2011 (Sławiński, Dębowski, 2013).

In France, the requirement for a gradual convergence of national education systems towards the European overarching framework led to a debate that continued for many years. The most concrete achievement to date is probably the full adoption of the Bologna levels for higher education degrees and the successful introduction of ECTS credit systems. Meanwhile, the French VET system, firmly based on principles dating back to the 1960s and strongly regulated by the State, had to find its way between national and European policies that were not always entirely compatible with each other.

While the Lisbon Process and the ensuing EC recommendations had at their heart citizen and worker mobility, comparability between national training systems and the harmonization of qualifications, French policies were always supported by very pragmatic macro-economic considerations and objectives. The most important priority was the fight against unemployment, often reflected in the will to provide the productive sector with the most fitting competences, thereby reducing labour market demand-supply mismatches. Different political priorities sometimes gave the impression that France was holding back from the Lisbon harmonisation process, distrusting European initiatives and clinging proudly to its reputation as an exception (Bouder, Kirsch 2007). However, we will show that changes that took place in France as it adapted its qualifications system were far from contradicting the processes launched at EU level, even though they were seldom acknowledged in the political discourse as responses to EU recommendations.

The French system actually anticipated many of the European guidelines. Since the 1960s, France has gradually developed a national qualifications classification (which later became a proper “national qualifications framework” using the European terminology). This classification made it possible to gradually bring general and vocational training closer together, to provide continuity between initial and continuing vocational training and to integrate the validation of prior experience according to lifelong learning principles. Standards for occupations have also been drawn up based on “learning outcomes”, using competence concepts to describe these outcomes (Bouder, Kirsch 2007).

In the next sections, we will describe some of the relevant circumstances that led to the adoption in France of the national qualifications framework (NQF) introduced by article 31 of the Act of 5 September 2018 on the “freedom to choose one's professional future”. The process of adopting the new framework lasted almost ten years. As a national centre of expertise on qualifications, training and employment, Céreq had the opportunity to be involved in the process leading to its adoption. Drawing on Céreq’s past research, internal documents and notes but without any claim to being exhaustive, it is possible to reconstruct some of the relevant moments of this debate, highlighting examples of the possible tensions and compromises that adherence to European goals creates for national priorities.

2 The road towards a fully accomplished French Qualifications Framework

Introduced in 2018, in conjunction with a wide array of VET policy reforms (see section 4), the national framework of vocational qualifications is “the new classification to which all ministries and certifying bodies must refer when determining the level of competence of professional qualifications” (Ministry of Labour website).

The genesis of this new framework was long and winding. France benefits from a centralised and firmly established system of qualifications whose founding principles date back to the early 1960s, when the establishment of a grid of training levels was put on the agenda and finalised in 1969. A few years later, in July 1971, the French government issued its first legislation on continuing vocational training (the Act on Training and Social Promotion). The almost simultaneous appearance of these two structuring measures made it possible to bring general and vocational training closer together, in such a way as to complement the traditional concept of initial education with a new vision of lifelong vocational training. Many years later (between 1985 and 1992), the introduction of the system for validating prior experience (VAE) ultimately paved the way for an integrated lifelong learning vision in the French education and training system.

The classification adopted in 1969 served very well for almost 50 years. It rapidly became a widespread reference tool for classifying qualifications and training courses according to job categories. Initially conceived as a forecasting tool intended to guide student enrolments and regulate flows into the education system, it gradually extended its functions to become a standard for training and employment relations, a standardized recognition instrument capable of 'regulating the conditions of exchange and valorisation in a market' (Affichard 1983). The 1969 classification did indeed acquire stakeholder legitimation over time, which few people called into question. As the starting point for this classification was a desire on the part of both public and private stakeholders to obtain indicators to measure, at a time of shortages of skilled workers, the shares of the population to be enrolled at different levels of qualifications[1], it relied naturally in its construction on the hierarchy of diplômes that had more stable definitions (unlike jobs) and were transposed into training levels. (Paddeu, Veneau, Meliva, 2018).

It is actually surprising to discover how major goals of national frameworks, as indicated in EC recommendations released decades later, were already being pursued by the French classification. As stated in EU policy, the classifications (or frameworks) made national education systems “easier to understand”, thereby promoting transparency, visibility, stakeholder sharing and mobility in (national) labour markets. All these objectives seemed to be achieved in France with the former classification. Nevertheless, there was one single major mismatch, namely that the classification was centred essentially on diplômes (i.e. formal qualifications) and was therefore strongly emphasised the length and content of training programmes and not, as the later Lisbon doctrine stipulated, on the attestation of specific competences possessed by holders of formal qualifications and formalised as “learning outcomes”.

The strong stakeholder legitimation and the 1969 classification’s partial compatibility with the basic principles of the Lisbon process can explain why the revision process took a relatively long time (about 10 years). How was the process of transition towards a Lisbon-like qualification framework triggered in France? To what extent did EU policies contribute to change?

Some authors (Maillard 2019; Kirsch, Kogut-Kubiak 2010; Bouder, Kirsch 2007) suggest that the introduction in 1985 of the vocational baccalauréat was a landmark heralding a new approach to vocational training characterised by the concept of “occupational descriptors” that make a direct connection between a set of competences and a specific occupation. For the first time it was stipulated that occupational descriptors had to be the basis for curricula standards and defined well before the corresponding training modalities or pedagogical approach. Thus an autonomous certification process was proposed as a universal marker easily understood by all labour market stakeholders and attesting to the competences of individuals and their fitness for a particular job, regardless of how their competences were acquired and the training format that might have led to them (school-based training, apprenticeship, informal learning, etc.).

Later on, the French law on social modernization (Act no. 2002-73 of 17 January 2002) strongly supported the gradual extension of occupational standards to all vocational qualifications. The Act introduced a logic centred on abilities that was gradually to replace a logic centred on knowledge (CNCP referencing report 2010). Two major innovations were introduced: the National Register of Vocational Qualifications (RNCP) and procedures for the validation of prior experience (VAE), which had been revamped and extended to include qualifications other than those awarded by the Ministry of Education. The quality procedures introduced for the incorporation of qualifications into the RNCP adopted a clear competences-based approach by making it mandatory to set up occupational standards organised as learning outcomes descriptors and ranking certifications accordingly into “levels”.

As we have seen above, the construction of the European Qualifications Framework (EQF), initiated in 2004 and adopted in 2008 by the European Parliament, did not find France unprepared. Even if many of the aspects introduced by the European regulations were already present in the French context, the introduction of the EQF triggered a debate in France on the need to overhaul the 1969 classification of levels (Labruyère 2013). The EQF structure was clearly based on an Anglo-Saxon tradition (Cedefop 2005) that was unfamiliar to French stakeholders, in particular the vertical organization of levels (from 1 to 8, exactly the opposite of the French classification going from V to I) and the contents of horizontal descriptors divided into knowledge, attitudes and competences (Charraud, 2004).

It was presented as an overarching framework that transcended the boundaries between vocational training and general education which were, at that point, still quite separate in France. It was intended to go even further, by being conceived as an inclusive framework encompassing non-formal training, which was a particular sensitive issue in France, where the State was particularly cautious to open up its register to private sector certifications, most of which used alternative forms of learning provision rather than the formal approach[2]. What is more, the EQF proposal definitively broke with the “knowledge input” approach based on the number of years of study and training. As a result, the 1969 classification appeared suddenly “outdated”. Experts varied in their opinions on the new framework, ranging from contempt, with references to "the antiphon of the free movement of workers" (Mehaut, Winch, 2011), to a feeling of innovation that was still missing in the 1969 classification (see next section).

Nevertheless, more pragmatically, the urgent question was how to reconcile a well-established system, recently reformed and improved by the introduction of the RNCP, with the European injunction to make it compatible with the EQF. As Paddeu, Veneau, and Meliva (2018) pointed out, no French legislation had ever explicitly mentioned the existence of a “national qualification framework”, the only reference being to a national register of vocational qualifications, namely the RNCP. The European obligation to report actions undertaken at national level with the aim of completing the Lisbon Process forced French institutions to address the issue. The 2010 report on referencing the French system of certifications to the European Qualifications Framework mentions, perhaps for the first time, the term “qualification framework”. This document, much to readers’ astonishment, clearly states that “it is the national register of vocational qualifications (RNCP) that constitutes the French national framework” (CNCP, Referencing report, 2010, p. 4).

Thus, as a result of the referencing process, the National Commission for Vocational Certification (CNCP)[3], which was responsible from 2002 to 2018 for the maintenance and management of the RNCP, stated in 2010 that: “After a certain number of analyses, it was decided that a correspondence [with the EQF] should be established between the levels on a “block to block” basis, i.e. by lining up each level of the French framework with a level of the European framework, when this was possible” (CNCP, Referencing report, 2010).

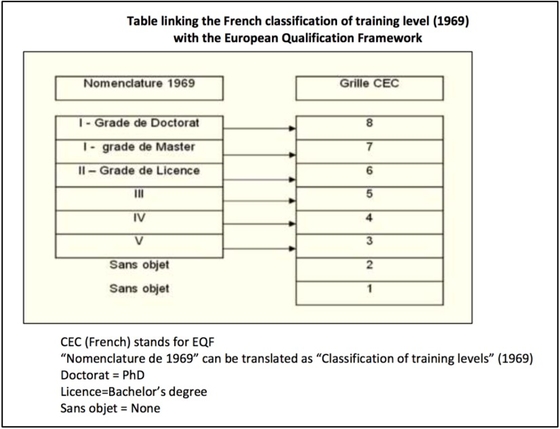

Figure 1: Linking the French classification of training level (1969) with the EQF (Source: Paddeu, Veneau, and Meliva, 2018)

Figure 1: Linking the French classification of training level (1969) with the EQF (Source: Paddeu, Veneau, and Meliva, 2018)

However, this apparently simple matching procedure did not solve all the pending issues. First of all, not all qualifications registered in the RNCP were eligible to be transferred to the EQF levels grid for the simple reason that, in some specific cases, they had no level. This applied to vocational qualification certificates (CQPs) issued by organisations jointly run by the social partners, which do not feature any levels because they were intended as add-on modules focused on a limited number of competences and learning outcomes. In addition, general education diplomas (i.e. the general baccalauréat) are unquestionably classified at a particular EQF level but do not feature in the RNCP because they are not intended to be vocational certifications but simply to qualify holders to enter higher education. As such, they are not consistent with the notion of vocational qualifications relating to specific jobs or careers. The reference report suggested a not fully satisfactory solution to this mismatch, stating that “In order to determine the corresponding level in the EQF, it will be advisable to refer to the level in the national lists. Only certifications featuring a level in France could be identified in the corresponding EQF level” (p.23).

There was a second conceptual problem. The first two levels of the EQF did not correspond to any kind of French certification whatsoever and, what is more, their mere existence was full of political implications that could have potentially undermined the social partners’ agreement that no certification for vocational purposes could have had a level lower than the lowest level of certification issued by the French ministry for education (level V, corresponding to level 3 of the EQF). As collective bargaining was based on the hierarchy of certifications defined by the 1969 classification, and taken as basic pillars for the definition of wage grids for each occupation, the idea that the EQF could have introduced lower levels (EQF 1 and 2) that would have possibly legitimated the presence of low-skill and low-paid jobs, was of course not acceptable to the unions and to labour market stakeholders in general.

3 From the EQF referencing report to the new framework project

The release of the 2010 referencing report was not the end of the debate on the need to modernise the French framework. The debate was of course fuelled by the European input, fostering a growing view that the 1969 classification was no longer able to link the French system to the European and international frameworks. The CNCP, after having supported the legitimation of the status quo endorsing the 1969 classification as the French Qualifications Framework, acknowledged the growing consensus and took charge of the continuing debate. The CNCP actively proposed a new classification project closer to a proper qualifications framework.

After several hearings of an expert working group set up for this purpose, the CNCP released in 2013 a "draft classification of French certification levels" which, after a quick reminder of the European objectives, listed a series of objectives "shared" by all the stakeholders participating in the working group. These objectives echoed internal issues, in particular the need to respond to the evolution of the labour market, to reflect the evolution of university qualifications, in particular the PhD (not explicitly included in the 1969 classification), to acknowledge the value of private professional qualifications (the CQPs) by attributing them to a level and to provide “unambiguous” signals in the labour market (CNCP 2013). The last point was meant to reaffirm that the use of the classification as a marker of wage levels was to be preserved[4] as a significant reference point in collective bargaining (Caillaud, Quintero, 2013). Thus, national considerations still seemed to prevail as leverages for innovation.

It should also be noted that in this particularly enlightening CNCP text, the European dimension reappears when it is noted that France must ensure the clarity of the process of constructing international qualifications in which the country was to be asked to participate. To this end "it is proposed to work with descriptors, a method currently used by all qualification frameworks" (CNCP 2013).

The new grid proposed by the CNCP was composed of 7 levels, two of which were new, one corresponding to the disaggregation of level I of the 1969 classification, taking into account the PhD and other qualifications corresponding to a very high level of technicality and complexity, the other, at the opposite end of the range, corresponding to the lowest entry level, situated below level V of the 1969 classification. The CNCP was therefore opposed to the extension of the French framework to the 8 levels of the EQF, refusing to add a level 1 and limiting any extension of the levels to level 2 of the EQF. The same document also explains that this choice was also supported by international benchmarking work that showed how the Scandinavian countries had made the same choice.

The second striking innovation was the introduction of the new level descriptors, based on those of the European framework and formalised as learning outcomes, but not without reference to French exceptionalism in order to make an important distinction. The “knowledge” descriptor, the first column of the European framework, was considered irrelevant to the French situation, in which there was perceived to be a direct correspondence between qualifications and occupations. Knowledge was supposed to be incorporated into the first proposed descriptor: professional competences (which would group together know-how, attitudes and theoretical knowledge). The remaining two descriptors were focused on transversal competences (the second) and autonomy (the third). The organisation of the three descriptors was thus modelled on the European structure without, however, reproducing the same contents and definitions.

The new framework project was not well received by CNCP stakeholders and several criticisms emerged. Most of these focused on the inclusion of "level 2" (Labruyère 2013). This proposition, which was entirely compatible with the architecture of the EQF (without, however, pushing it to the point of adopting a level 1), once more confirmed the concern to move against the social partners’ consensus on the connections between training achievements and wage grids. Thus, the new classification would have reintroduced vocational qualifications that could correspond to low-skill jobs below the 'first level of qualification' (according to the terminology usually used in collective agreements) and "without diploma". Nevertheless, conceded the CNCP, the existence of level 2 certifications should have depended on the interest of the labour market stakeholders in this type of certification. The practical uses of this new level 2 would have been left to social dialogue.

Céreq, invited by the CNCP to give an opinion on the subject[5], expressed concerns, stressing that the proposal would have put back on the table the question of the gap between skilled and unskilled work and demolished the benchmark principle of the "first level of qualification", erected around the CAP of level V (Labruyère 2013). In its memorandum of 10 October 2016, Céreq also stated that this level could only be used to fill jobs listed as "unskilled", which would constitute a break with the French conception, widely shared by the social partners, of what a vocational certification is, namely recognition of a specific occupation expressed as a full set of competences and skills.

Furthermore, the creation in 2014 of the so called Inventory[6], as a supplement to the RNCP, would have made it possible to give visibility, and even a value on the labour market, to "partial certifications" comprising a limited number of "competence blocks", thus providing their holders with a signal on the labour market and a step on the way towards a full qualification (in the French conception expressed in the Céreq memorandum) as part of a process of gradual capitalisation of the blocks. The Céreq document insisted on the uselessness of "level 2 vocational certifications to recognise the competences of unqualified employees who wish to progress in their occupation" and upgrade towards a full certification.

Regarding the organization of the new descriptors, the choice to not include a separate descriptor on “knowledge” was also questioned. The CNCP’s starting point was the assumption, rooted in the principles of the French system, that only “applied knowledge” can be considered “vocational”. That was indeed the reason because the RNCP included nothing but vocational qualifications that, at different levels, provided access to the labour market. Theoretical knowledge per se is transmitted through general education (not included in the RNCP). In order to be effective in vocational certifications, knowledge must take the form of practical skills, expressed of course as learning outcomes.

In view of the Lisbon convergence process among national qualifications frameworks, the fact that this descriptor was not chosen created a bias in the transnational comparability and would have been hard to justify. The CNCP’s choice clearly generated a tension between national exceptionalism and European priorities. Would it have been possible for France to avoid creating a "knowledge" column when this descriptor appeared in the European Qualifications and Lifelong Learning Framework? We do not have documents recording the state of the debate within the CNCP on this specific point. What is likely is that CNCP members (Céreq for sure was among them) showed scepticism in pursuing the path of a sharp divergence from the EQF descriptors. This was probably the reason why the CNCP soon proposed an alternative system of descriptors.

By way of compromise, the CNCP introduced an “associated knowledge” descriptor but it was left in third position. It would be a question for the CNCP to adopt a mode of presentation consistent with the French approach to the construction of qualifications. Indeed, as Céreq argued (Céreq, 2016), the primary use of the framework and its descriptors is to classify qualifications produced elsewhere, by mobilising, in parallel, the three descriptors. It was important to re-establish the order of presentation retained by the EQF, as follows: Knowledge, know-how and autonomy-responsibility, so as to facilitate the work of European comparison. In this hypothesis, the addition of the term "associated" could give rise to misunderstandings, which is why it was proposed to stick to the term “knowledge”, but without changing the CNCP’s proposed definition, which associated this knowledge with the work activities carried out.

Table 1: Structure of EQF descriptors

|

Knowledge |

Skills (aptitudes) |

Competences (autonomy) |

|

Theoretical and/or factual and/or applied knowledge |

Cognitive skills (based on the use of logical, intuitive and creative thinking) and practical skills (based on dexterity and the use of methods, materials, tools and instruments). |

Competences in terms of taking responsibility and autonomy. |

Table 2: First CNCP proposition (2013)

|

Vocational competences |

Transversal competences |

Autonomy |

|

Know-how and applied knowledge |

A series of elements (introduced gradually in accordance with changes in level) such as teamwork, supervision, professional development of staff, transmission of information, ability to work according to the new collaborative methods and the introduction of strategic analysis and management skills. |

Ability to organise one's work in relation to the work group and to management. Ability to organise one's learning project within the framework of lifelong learning. |

Table 3: Second CNCP proposition (2016)

|

Know-how |

Autonomy - responsibility |

Associated knowledge |

|

Progression in the following areas: - the complexity and technicality of a task, an activity in a process, - the level of mastery of the professional activity -mobilising a range of cognitive and practical skills -know-how in the field of communication and interpersonal relations, in the work context. - the ability to transmit know-how. |

Progression in the following areas: - the organisation of work - response to unforeseen events - understanding the complexity of the environment -understanding the interactions among different occupations and professional fields, being able to organise one's own work, correct it, or give guidance to supervised staff. -participation in collective work - level of supervision |

Progression in knowledge necessary to carry out the work-related activities (processes, materials, terminology relating to one or more fields as well as theoretical knowledge). |

Source: Own compilation based on Céreq 2016

4 The adoption of the new qualifications framework in the context of a reformed VET system

The most recent reforms of the system of VET governance in France had a catalytic effect on the introduction of the new French National Qualifications Framework. Its adoption is embedded in this process, which got under way with the adoption of the law on the "freedom to choose one's professional future", promulgated on September 5th, 2018.

The new law has ambitious objectives: to face the challenge of employment and the need to raise skill levels by targeting job seekers and the least qualified as a priority, simplifying the system and improving the rights of individuals to access lifelong training. These ambitions led to an unprecedented overhaul of the training and learning system, in which a new governance framework was put in place and the remits of the actors involved in the governance of VET were reconfigured. Since the adoption of the new qualifications framework is strictly linked to the reform, it is important to present some of the new law’s key provisions.

One of the main turning points was the creation of a new national agency called France Compétences, which became operational on 1st January 2019 as the only organisation responsible for the financing, regulation and improvement of the vocational training and apprenticeship system. It is set up as a public administrative body with legal personality and financial autonomy, under the control of the ministry responsible for vocational training. Its strategic orientations are determined by a quadripartite system of governance composed of representatives of the State, the regions, national and inter-occupational trade unions representing workers and employers and qualified persons. The new body was a merger of various former organisations, among them the CNCP, and in consequence took over responsibility for the National Register of Professional Qualifications (RNCP), which involves overseeing the registration of certifications issued by private entities as well as ensuring overall consistency and maintenance of the register[7] .

The 2018 law also modified the personal training accounts (CPFs). From 2014 onwards (Act of 5 March 2014 on vocational training, employment and social democracy), all economically active citizens residing in France, from the moment of entry into employment until retirement, have enjoyed the right to training funded by means of a personal account that can be used on their own initiative and at any time. CPFs are permanent and unrelated to changes in occupational and labour market status. The 2018 reform converted the CPF from a time account into a euro account. One of the predicted major consequences of the monetisation of the CPF is the proliferation of market-oriented training offers that users can buy directly via a smartphone application. In order to be eligible for the CPF, the training body must acquire an accreditation permitting it to issue certifications registered in the RNCP, the only ones that can be found on the smartphone application.

In the new scenario, France Compétences manages the accreditation of training providers and the RNCP in order to ensure the quality of VET delivery and the certification system. For its part, the reformed CPF guarantees wide access to training opportunities of all scales, levels and formats, all them RNCP-certified. This is clear evidence of the gradual shift of French policies from what we can call the holistic notion of qualifications (a full set of competences and skills) certified by a given level and universally recognized as a reliable marker in the labour market to a system where “full” qualifications are broken down into separate blocks of competences to be acquired separately. This new format should enable citizens to benefit from lifelong learning in order to progress gradually towards higher qualifications levels.

These developments were (quite obviously) motivated by a great concern to improve workers’ employability as much as possible in an economy very exposed to rapid change, whether digital, environmental, demographic or related to health and safety. The latest reforms strongly promote labour market mobility by supporting greater modularisation (the block-wise division of State certifications is underway) and openness to non-formal training formats. The idea that the new blocks-based approach will help introduce elements of flexibility into the skill acquisition process is a shared opinion. We can even talk of a “French path to flexicurity” (Gazier 2008; Berthet, Vanuls, 2019), reaffirmed by these recent developments and opening up training and re-training paths for job seekers.

The establishment of a training market promoted by the CPF, the re-organisation of qualifications into blocks of competences, combined with relevant earlier developments (the creation of an inventory aside of the RNCP and the gradual increase in sector-level CQPs), made the adoption of a modernized national qualifications framework the only way to integrate all these new developments in a coherent way.

Introduced by the 2018 Act, the brand new NQF is mentioned in the third paragraph of article L. 6113-1 of the labour code, where explicit reference is made to the coordination and principles of the council recommendation of May 22, 2017 concerning the European Qualifications Framework for lifelong learning (EQF). What is more, the labour code specifies that "professional qualifications are classified by level of qualifications" at the same time: - “with regard to jobs"; - and "correspondences with the certifications of the States belonging to the European Union" (EU). Thus, the new act introduces a perfect match between national and European priorities in the national code.

Compared with the project discussed at the CNCP, the version of the NQF that was finally adopted brings some slight but meaningful changes. It finally stabilises the sequence of descriptors in a way that is much more consistent with the EQF, as described below.

Table 4: The French qualifications framework descriptors (2018)

|

Knowledge |

Know-how |

Responsibility and autonomy |

|

The complexity of the knowledge associated with exercise of the professional activity in question |

The level of know-how, which is assessed in particular according to the complexity and technicality of a task or activity in a work process; |

the degree of responsibility and autonomy within the work organisation. |

Source: own compilation based on State decree of 9th January 2019

Quite surprisingly, the new NQF is divided into 8 levels exactly as the EQF, putting an end to the discussions and uncertainties about the introduction of a level 2; it even introduces a level 1, which corresponds to the mastery of basic knowledge[8]. Level 2 is not intended for full qualifications but is supposed to recognise “abilities to perform simple activities and solve common problems using simple rules and tools by mobilising professional know-how in a structured context” (Ministry of Labour). The adoption of levels 1 and 2 is the final recognition of a changed VET context strongly oriented to a large and inclusive system of certifications that also recognises partial and “short” certifications intended to meet short-term labour market needs.

Table 5: Correspondence between the 1969 classification’s intermediate levels and the 2018 National Qualifications Framework (VET system levels)

|

1969 Classification |

2018 NQF |

|

Level V |

Level 3 |

|

Level IV |

Level 4 |

|

Level III |

Level 5 |

|

Level II |

Level 6 |

Final evidence of the process described above is the regulatory decision to identify a level for all registered CQPs in order to fully integrate them into the RNCP in the same way as any other qualification: “by constituting a single national space integrating all the contributors to the certification system, the RNCP is the reference tool for all the actors involved in the employment-skills relationship at the national and international level as well as for the public and companies” (France Compétences).

5 Conclusions

At the turn of the 1990s, French leaders were forced to consider employment as the highest "national priority" (Paddeu, Veneau, Meliva 2018). As a result, it was assumed that fighting unemployment and, more specifically youth unemployment, would be the main policy driver. It was no longer a question of simply accrediting and recognising training programmes or, more precisely, the duration of training; the focus had now shifted to the "learning outcomes" of these programmes, with the aim of providing the labour force with the necessary competences required in the labour market. The modernisation of the French system progressed reform by reform. The system was made more flexible by introducing private qualifications, including a variety of non-formal training options, by deconstructing national qualifications into blocks of competences that could be acquired through the use of a personnel training account (CPF) and ultimately accomplishing the reform of the qualifications framework.

In the present article, we have described the long-lasting genesis of the new French NQF. We have analysed this process from an historical perspective and indicated some of its milestones. In doing so, we have provided an insight into the basic principles of the French system showing how it is deeply rooted in macroeconomic considerations and the general principles of social justice. Nevertheless, these principles have changed over time, with a shift from a concept of the State as ultimate guarantor of equal opportunities for all to a more liberal approach in which individual citizens are masters of their own choices in terms of training and career. These personal choices should be backed up by a larger offer of public guidance services, a state-regulated training offer, quality assurance processes and stronger involvement by the social partners.

This journey through the evolution of the French system evolution clearly shows that even if the European policy agenda (based on promoting mobility and guaranteeing comparability of qualifications) was not at the core of the reform process, it gradually became part of the debate and was increasingly referred to in CNCP and France Compétences working documents. The final result was gradual alignment with the Lisbon principles, even though they were not the main drivers of reform.

The French framework today is much more in line with and comparable to the European EQF, even though VET systems remain very diverse and fragmented across Europe. The harmonisation of qualifications frameworks has certainly not solved the bigger issue of a common European space for VET, nor will it prevent France from reaffirming the exceptionalism of its system.

References

Affichard, J. (1983), Nomenclature de formation et pratiques de classement. Céreq, Formation Emploi n.4.

Berthet, T., and Vanuls, C. (2019). Vers une flexicurité à la française ? Lest/Octares.

Bouder, A., and Kirsch, J-L. (2007). Drawing up European competence standards. Some thoughts about the experience gained in France, Céreq, Training and Employment n.78.

Caillaud, P., Quintero, N., and Sechaud, F. Quelle place, quel rôle et quel statut du diplôme dans les grilles de classification des branches professionnelles ? CPC Info n. 53.

Charraud, A.-M. (2004). Note destinée à la CNCP, Céreq working document.

Céreq (2016). Consultation des membres de la CNCP sur la proposition de nomenclature des niveaux de certification. Avis du Céreq. Working document.

CNCP (2010). Referencing of the national framework of French certification in the light of the European framework of certification for lifelong learning.

CNCP (2013). Projet de nomenclature des niveaux de certification français. Working document.

Cedefop (2005). European reference levels for education and training promoting credit transfer and mutual trust Study commissioned to the Qualifications and Curriculum Authority, England.

Gazier, B. (2008). Flexicurité et marchés transitionnels du travail: esquisse d’une réflexion normativ, Travail et Emploi, no 113.

European Commission. (2006). Implementing the Community Lisbon Programme. Proposal for Recommendation of the European Parliament and of the Council on the establishment pf the European Qualifications Framework for lifelong learning.

European Parliament and Council. (2008). Recommendation on the establishment of the European Qualifications Framework for lifelong learning.

European Council. (2017). Recommendation on the European Qualifications Framework for lifelong learning and repealing the recommendation of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 April 2008 on the establishment of the European Qualifications Framework for lifelong learning, (2017/C 189/03).

France Compétences (2019). Note relative au cadre national des certifications professionnelles.

Kirsch, J-L., Kogut-Kubiak, F. (2010). Vingt ans de bac pro: un essor marqué par la diversité. Céreq, Bref n. 270.

Labruyère, C. (2013). Rénovation de la nomenclature des niveaux de certification : objectifs poursuivis et enjeux, Céreq working document.

Maillard F., Moreau G. (2019). Le bac pro – Un baccalauréat comme les autres ? Céreq/Octares.

Méhaut, P., and Winch, C. (2011). EU initiatives in cross-national recognition of skills and qualifications in Brockmann M., Clarke L., Winch C. Knowledge, Skills and Competence in the European Labour Market, Routledge.

Ministère di travail (2019) Cadre national des certifications professionnelles. Online: https://travail-emploi.gouv.fr/formation-professionnelle/certification-competences-pro/article/cadre-national-des-certifications-professionnelles (10.09.2020).

Ministère du Travail (2019) Décret no 2019-14 du 8 janvier 2019 relatif au cadre national des certifications professionnelles.

Ministère du Travail (2019) Arrêté du 8 janvier 2019 fixant les critères associés aux niveaux de qualification du cadre national des certifications professionnelles.

République Française, Loi n° 71-575 du 16 juillet 1971 portant organisation de la formation professionnelle continue dans le cadre de l'éducation permanente.

République Française, Loi n° 2002-73 du 17 janvier 2002 de modernisation sociale.

République Française Loi n° 2014-288 du 5 mars 2014 relative à la formation professionnelle, à l'emploi et à la démocratie sociale.

République Française, Loi n° 2018-771 du 5 septembre 2018 pour la liberté de choisir son avenir professionnel.

Paddeu J., Veneau P., and Meliva A. (2018). French National Qualifications Framework, Céreq Etudes, n° 19, 2018.

Sławiński S., and Dębowski H. (2013). Referencing the Polish Qualifications Framework for lifelong learning to the European Qualifications Framework.

[1] The term is used here in the way it is used in French language sense, as a “fixed set of tasks defining a particular job”.

[2] Since 2002, organisations representing the social partners (especially representatives of manufacturing and service industries) had been allowed to include their own Vocational Qualifications Certificates (CQP) in the RNCP. These CQPs were already a common currency in the French labour market and could be registered by the industry in question on a voluntary basis. They were not classified by level in the RNCP.

[3] The CNCP, which replaced the former Technical Homologation Committee (CTH), was the national authority responsible for ensuring the coherence, complementarity and updating of certifications registered in RNCP, checking that they were adapted to occupations and work organisation changes. Registration was also open to private providers submitting a specific demand for certification registration.

[4] In collective bargaining, this principle is made explicit in the constitution of the so-called grading criteria grids (grilles à critère classant), which are the ultimate results of job analyses conducted at industry or enterprise level.

[5] Until 2018, Article R335-24 of the Education Code determined the composition of the CNCP committee, including representatives of the government, employers and employees. In addition, 15 qualified members also took part in the CNCP work without voting rights, Céreq among them.

[6] Act No. 2009-1437 of 24 November 2009 relating to career guidance and lifelong vocational training requires the CNCP to identify “qualifications and accreditations that correspond to the cross-cutting competences used in the workplace”. What it was looking for exactly was any means of certifying vocational competences that was not linked to a full qualification (i.e. to an occupation that is recognized in an industry-level agreement), not included in the French classification of 1969 and usually involved short courses. However, Act No. 2014-288 of 5 March 2014 relating to vocational training, employment and social democracy introduced a new register, “the Inventory”, to identify these types of qualifications (Paddeu, Veneau, Meliva 2018).

[7] The RNCP is made up mainly of certifications issued by public certifiers (ministries) and registered "by right". Nevertheless, private entities can ask for registration of their certifications following a submission procedure regulated by the CNCP (and since 2019 by France Compétences), which was responsible for issuing a “notice of conformity” to the standards of the registry (registration on demand).

[8] It is stipulated, however, that the certifications corresponding to this level are not related to a specific trade and cannot be registered in the RNCP (France Compétences).

Zitieren des Beitrags

Sgarzi, M. (2020): French exceptionalism tested against the Lisbon strategy principles. The case of the Qualifications Framework implementation process. In: bwp@ Berufs- und Wirtschaftspädagogik – online, issue 39, 1-16. Online: https://www.bwpat.de/ausgabe39/sgarzi_bwpat39.pdf (17.12.2020).